|

|

|

The Severn Railway Tunnel.

Chapter 4 - Highs and Lows.

Although of all of the year of 1880 had been spent shutting out the Great Spring, other work had progressed on the surface. As the workforce grew at Sudbrook, so the need for housing the men increased. Several houses were built which also gave additional provision for lodgers, in addition to houses for the foremen and a large house for the foreman of the tunnels, Joseph Talbot. As Walker was a deeply religious man, a mission hall was erected to hold 250 people together with a day school and a Sunday school. Road links were improved, encouraging tradesmen from Chepstow and Caldicott to sell provisions to the new community.

Now that the Great Spring had been controlled, the year of 1881 began on a note of optimism. For extra security against water in the workings though, additional headwalls were later to

be built in the headings; one just east of Richardson' headwall 350 yards from the Old Shaft and another built mid-way between the Old Shaft and Richardson's headwall for although the greatest concentration that was seen at the works up to that time had been removed, the pumps at the shafts had to kept in operation to dispose of the water seeping from the rock.

Coal stocks used for firing the boilers of the pumps were never kept too large since deliveries of coal were readily available from mines nearby, but on the afternoon of the 18th of January, a massive snowstorm swept across all areas of England and Wales crippling the whole country. Although the main line running into Portskewett opened the next day, the branch line to Sudbrook was under 4 feet of snow as were the roads in the immediate area. The coal stocks subsequently dwindled so much that coal was begged and borrowed from all sources in the neighbourhood supplemented by timber from the works. After the snow, came a severe frost which prevented any work on the surface until an improvement in the weather on the 28th of January.

A new shaft at Sudbrook, to be called the New Winding Shaft was sunk and a 9 feet heading was driven from this shaft to join the 7 feet headings. This area was then enlarged to an 18 feet tunnel allowing extra movement of the skips to and from the New Winding Shaft.

On the 9th of May 1881, Walker and Joseph Talbot opened the door in the headwall that Lambert had closed five months earlier. Generally the heading was in reasonable condition but about 1¾ miles from the Old Shaft, the roof had fallen in for a considerable distance and eventually blocking the heading. Due to this roof fall, the perforated air pipes that ran along the side of the heading were choked by dirt and produced such poor air quality that the lights they carried went out. Returning back to the shaft in the darkness reminded both of them of Lamberts heroic efforts.

After cleaning the air pipes, the main heading could then be cleared of the debris. As it took the men almost one hour to push a skip loaded with timber to the roof fall, Walker ordered that they take their food with them so that they could complete the ten-hour shift underground. The Great Western men, who had been working on the tunnel for six years prior to Walker taking over the contract, were used to working eight-hour shifts and resented the fact that they were to have their breaks in the stifling air underground instead of coming up to the surface for their meals. This discontent grew when Walker's men were jeered at by the Great Western men, followed by assaults in the darkness. Finally on Saturday the 21st of May, the men gathered around the top of the main shaft and refused to go below. After an amount of debate, the men visited a nearby inn and, suitably primed, they returned to the pay office at the works. In all of this time, they never approached anyone in office regarding their grievance. Providing us with an insight into Victorian industrial relations, Walker told the men:

"Now, what do you fellows want?"

No answer.

"Now, tell me what you want, and don't stop hanging about here"

Then one of them said "We want the eight-hour shifts"

Walker's reply was "My good men, you will never get that, if you stop here for a hundred years. There is a train at 2 o'clock, and if you don't make haste and get your money you will lose  your train. You had better get your money as soon as you can, and go".

your train. You had better get your money as soon as you can, and go".

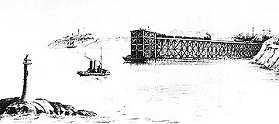

At this, the men collected their pay and promptly came out on strike, however, the following evening, the wooden pier for the New Passage ferry at Portskewett was burnt down. Many people straight away pointed the finger of blame fully on the strikers but Walker maintained that they were innocent. He later stated that there had been a long spell of dry weather and he suspected that a carelessly discarded match or sparks from the boiler of the luggage lift were to blame.

Walker was in one way thankful of the strike because, as he says ". . . it cleared away a number of bad characters who had gathered on the works . . .". In order to put some pressure on the strikers, Walker ordered all of the carpenters, blacksmiths and surface workers to stop work the following Tuesday. This obviously was a move the strikers had not expected and so on the Thursday, some of the men returned to the works while the main workforce went back the following day.

With a return to ten-hour shifts the headings were soon cleared, but where the roof had fallen in, the headings were constantly troubled by water as the strata was broken and fissures extended up to the river bed.

Copyright © by John Daniel 2013